When I first heard about heat pumps I’ll admit that I was a little puzzled about how they worked. I could get my head around geothermal energy because hot water coming out of the ground that had been heated by volcanic activity was no different to a traditional furnace heating up water to be used in a central heating system. All that’s really happening there is the substitution of heat from the earth’s molten core for the heat generated by a hot water boiler, the rest of the process is the same.

However, a heat pump does not generate heat – it moves heat from one location to another. Heating a building using cool (or even cold) water might seem too good to be true, but it is possible and is actually very common.

Heat pumps have been widely used for many years and, in fact, we all have one in our kitchen (our fridge). Heat pumps can also be used for more challenging jobs like heating a swimming pool (either with a GSHP or ASHP).

The science of heat pumps is well-established and can be explained using the laws of thermodynamics. At the most basic level, a heat pump moves heat from a heat source to a heat sink. What this typically means in practice is that the heat available in the ambient air outside, water in a nearby pond or river, or under the ground itself, is collected and then moved to a place where it can be used such as radiators or underfloor heating.

So how does a heat pump achieve this amazing feat?

Well, it all boils down to basic physics.

First of all, it is important to understand what heat is. Heat is a form of energy, which can be conceptualised as the amount of vibration that individual molecules or atoms exhibit. Remove all heat from a substance such as water and those molecules cease moving altogether. This is what happens at absolute zero, but absolute zero (0 degrees Kelvin or -273 deg C) is almost impossible to achieve. So even ice on a frozen lake in the north of Scotland has some heat in it.

If it is understood that heat is present even in cold river water, then the principle that this heat can be extracted and moved somewhere else starts to seem possible.

Under normal conditions, heat moves “downhill”, that is to say it moves from a hot location to a cooler location. That’s why your house cools down when it’s cold outside – some of the heat energy within the building moves downgradient to the cooler environment outside. What a heat pump does is use a small amount of (usually electrical) energy to reverse this natural process.

The easiest illustration of a heat pump at work is in your fridge. You may have noticed that the back of your fridge is normally warm to the touch. The reason for this is that the heat present within the fridge compartment is removed by the fridge, using electrical energy, and then dissipated via the coils on the back of the fridge. Simples!

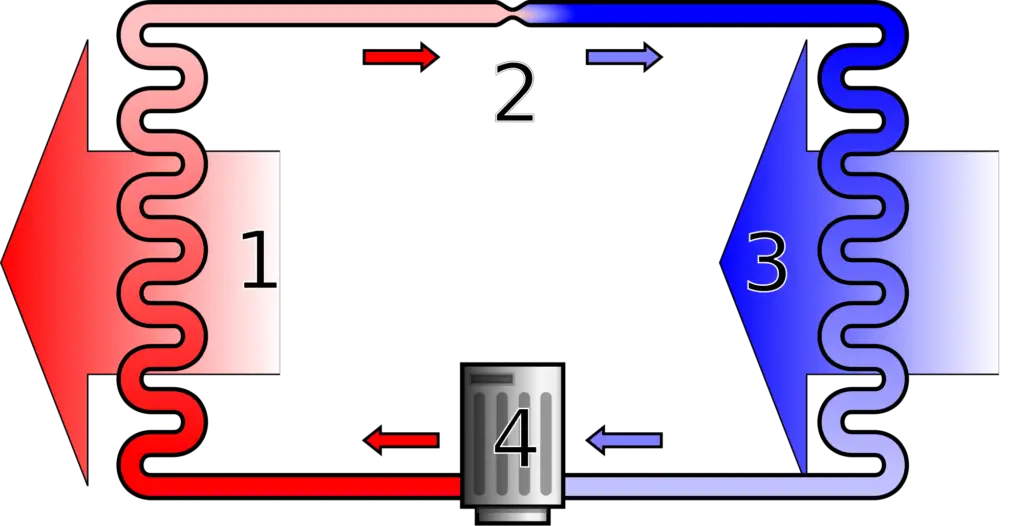

The process works by taking advantage of the properties of the refrigerant which is circulated around the heat pump’s components. The refrigerant absorbs heat from outside the building in the evaporator, where it changes state from liquid to gas. It then flows through a compressor, which circulates the high-pressure and high temperature refrigerant through a type of heat exchanger known as a condenser. In the condenser, the refrigerant changes from a vapour to a high-pressure liquid and gives off heat, which results in it cooling to a moderately warm temperature. At this point, the refrigerant is passed across an expansion valve, which reduces the pressure it is under. The low-pressure liquid then passes along the evaporator where it is provided with heat from outside causing it to boil and change state into a vapour, repeating the cycle over and over again.

The net result is that heat is absorbed from outside by the low-pressure liquid refrigerant in the evaporator coils as it boils, and the heat absorbed is then transferred to the inside of the building by the high-pressure refrigerant vapour in the condenser as it condenses to a warm liquid.

If you are interested in a more detailed explanation of how heat pumps work, please read my detailed article that covers the main scientific concepts involved, or check out the video showing the inner workings of a heat pump system.

Heat pumps come in a variety of different flavours. The main types being air-source, water-source and ground-source. Although they each get their heat from different sources (the clue is in the name folks!) they actually operate is very similar ways, thanks to those laws of physics that I mentioned earlier.